Managing COVID-19: Why poorer countries may drop out of industrialization

10 June 2020 By Frank Hartwich, Research and Industrial Policy Officer at the Department of Policy Research and Statistics (PRS) of UNIDO, and Anders Isaksson, Senior Research and Industrial Policy Officer at the Department of Policy Research and Statistics (PRS) of U

By Frank Hartwich, Research and Industrial Policy Officer at the Department of Policy Research and Statistics (PRS) of UNIDO, and Anders Isaksson, Senior Research and Industrial Policy Officer at the Department of Policy Research and Statistics (PRS) of UNIDO.

June 2020

This opinion piece is part of a series of articles by UNIDO's Department of Policy Research and Statistics.

Key Messages

- Industry will likely veer off the road to recovery in attempts to reach pre-COVID levels, requiring manufacturers to reshape their supply chain structure and, in some cases, to reorient production towards a different product mix.

- In response to COVID-19, manufacturers in developed countries are likely to implement business strategies with the aim of reducing the risks of sourcing from distant and unreliable suppliers such as those located in developing countries. Reshoring by developed countries as well as increased local and internal sourcing are likely scenarios, which developing countries need to take into consideration when crafting their own industrial recovery strategies.

- As a consequence of COVID-19, industries in developing countries face the risk of reduced engagement in GVCs. Alternatively, they could step up efforts to participate in value chains that offer real benefits for local investors, workers and society as a whole.

- Given that GVC participation of industrial firms in developing countries might decline, they may also be at higher risk of premature deindustrialization or of losing out on industrialization opportunities. Government and international support is thus necessary in areas of strategic importance so business can firmly remain on the path towards industrialization.

The aftermath of the coronavirus pandemic has the potential of being disastrous for industries worldwide, especially for smaller enterprises and for industry in less developed regions of the world. This opinion paper discusses these challenges and proposes strategies that developing economies could consider to stay on the road of post-COVID-19 recovery of their industries.

How industry gets infected by COVID-19

How will COVID-19 affect industry? It is important to ask this question now to mitigate the pandemic’s impacts and to prepare industry for recovery. Any recommendations in this regard must be underpinned by reliable data on industry’s post-crisis response as such data become available in forthcoming weeks to come. Nonetheless, the following COVID-19 effects on the economy may need to be considered:

- Effects of business closures: Due to curfews and social distancing measures, industries closed their doors or could not operate at full scale. This is especially true where the physical presence of workers in production is necessary. For example, factory activity in East Asia, Europe and the U.S. decreased significantly as a result of COVID-19.

- Effects of supply shortages: Industry cannot operate properly if businesses do not receive the supplies they need for production. As suppliers were also subject to restrictions, their output dropped as well. This became evident, for example, when Chinese suppliers ceased deliveries due to the COVID-19 lockdown of Wuhan.

- Effects of decreasing consumer demand: Consumer demand for industrial products—domestically and abroad—has fallen due to reductions in consumption and decreasing purchasing power.

- Effects of decreasing demand from industry: Businesses have witnessed a decrease in demand for their products—domestically and abroad—as buyers of intermediate products also faced restrictions in production and falling consumer demand for their products.

Due to global interdependence and interconnectivity, the above-described effects have led to a contraction in industrial activities worldwide. Recent analyses on the effects of COVID-19 containment impacts have led to further downward predictions of world GDP growth. (UNCTAD, 2020; CRS, 2020)

Ultimately, the duration and scope of COVID-19 containment measures and their impact on both the global economy and on national industries will determine whether industrial firms will be able to return to ‘business as usual’ (V shape recovery scenario) or whether they will need to undergo a certain degree of structural change and reorientation to adapt their current business models in order to venture on the road of recovery (U shape recovery scenario). For developing countries, this means to take a close look at two major risk factors related to the position of their industries in global value chains (GVCs): a) dropping out of GVCs, and b) premature deindustrialization.

a) The risk of dropping out of GVCs

Given the COVID-19-related disruptions in GVCs (Zanni, 2020) , the big global players have started to consider introducing more flexibility in their business models, e.g. with regard to their product lines, sources of inputs, people and skills (Rama Shankar Pandey, 2020), while others are looking to source inputs from less distant suppliers and to reshore their production. (Oxford Business Group, 2020; Belton, 2020). This could have serious consequences for less developed countries, as they may become increasingly excluded from participating in GVCs.

What is there to lose? Participation in GVCs means for developing countries that their firms exploit engage in production, learn business and get revenues from sales resulting in increasing gross domestic product. These benefits are potentially sizeable. There are, however, also some warning signs that the dominance of global buyers and suppliers in GVCs deprive certain firms—particularly in developing countries—from value capture. (Lee, Gereffi and Barrientos , 2014) Thus, GVC participation could potentially be a race to the bottom, with developing countries competing to become suppliers of cheap raw materials. (Rudra, 2008) Engagement in GVCs may be suboptimal for at least one of four reasons:

- Opportunity costs are associated with a country’s participation in GVCs, i.e. the country may find better opportunities to effectively use its domestic resources elsewhere, resulting in higher returns on investment and higher remuneration for workers.

- If public funding, i.e. taxes, are used to support firms’ engagement in GVCs, the cost of participation exceeds the resources of the participating firms.

- Calculations often do not include the total benefits and costs of GVC participation, but only the firm’s profit, disregarding any revenue accruing to workers (i.e. their remuneration), potential spillover effects and other externalities, incentives to suppliers, and so on. GVC participation may also entail negative externalities, for example, with regard to environmental effects.

- Business owners often do not have the option to invest their capital where it renders optimal revenues simply because investments are locked in physical infrastructure or due to a lack of knowledge to engage in other businesses. For example, an aquaculture producer with floating fishponds in Lake Victoria does not have many alternatives other than to produce tilapia and sell semi-processed filets in global markets, even if other activities (in other value chains) are available that promise higher returns.

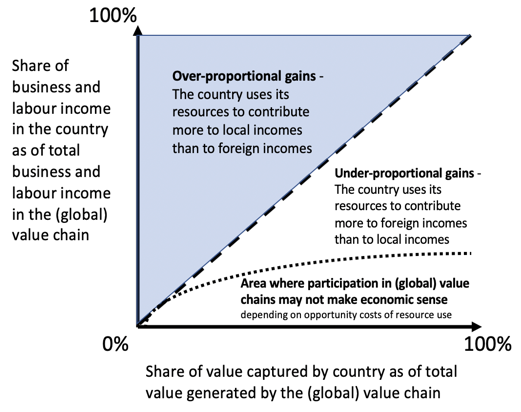

Figure 1 explores the possible relationships between the aggregate value a country’s businesses capture in relation to the total value generated in a GVC and the income of businesses and workers in that country in relation to the GVC’s total income. The illustration suggests that if the income of local businesses and workers outweighs the value added locally, engagement in the GVC should theoretically be beneficial for the country. However, situations may arise where the domestically generated share of income is lower than the value generated domestically.

Figure 1: Gains from participation in GVCs

Source: Authors

Now, what does this mean for developing countries in the era of COVID-19? Most likely, it will require more investment or sacrifices to have other countries sourcing products from developing countries. Also, due to the COVID-19 induced disruptions there will be less scope for countries that are small, new in business or geographically distant to recover from the crisis by joining or re-joining GVCs. This fact should encourage developing countries to re-evaluate the benefits of GVC participation and invest in physical and human capital and in innovation to participate in production processes where the benefits are real.

b) The risk of losing out on industrialization

The risk of simply remaining providers of raw materials or of transitioning to the service sector without having industrialized has become a threat for developing countries due to the COVID-19 outbreak. A country’s economy grows as it industrializes because of structural change – the shift of resources from low to higher productivity sectors. Yet there are concerns that industries in developing countries are deindustrializing prematurely (Dasgupta & Singh, 2006; Rodrik, 2015; Rodrik, 2016), thereby losing out on the benefits they would have reaped from further industrialization.

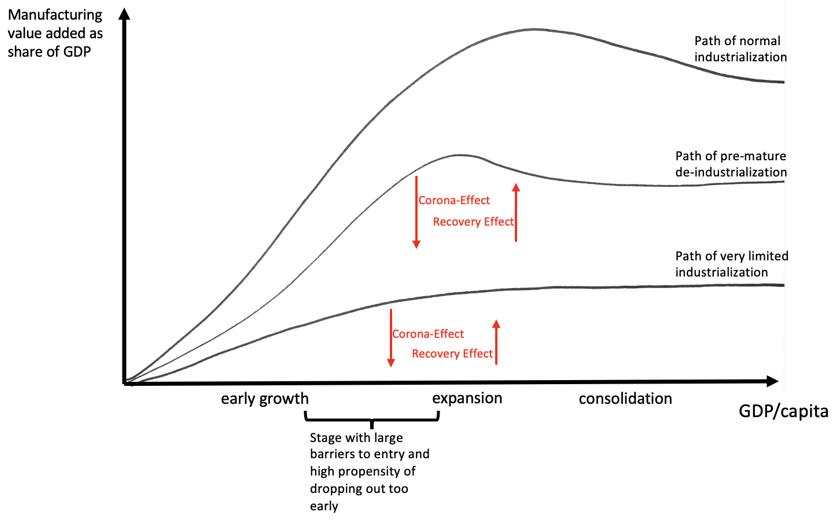

Figure 2 shows three typical paths of industrialization. The upper curve represents the “standard” path of industrialization followed by today’s industrialized countries. As countries’ gross domestic product rises over time, the share of manufacturing value added (MVA) in GDP increases at the expense of a reduction in the share of the primary sector (agriculture and mining) in GDP. Once the full effect of industrialization is achieved, resources start shifting to the tertiary sector (services). The middle curve illustrates the path of countries, including middle-income countries and those whose industries only recently developed, that run into difficulties for a number of reasons in their attempts to develop into already established markets. (UNIDO, 2008). During the stage of industrialization, i.e. as their GDP increases, they are unable to attain the same levels of MVA/GDP of earlier industrializing economies. The curve at the bottom of Figure 3 depicts those countries—many of which are found in the group of least developed countries—that do not achieve any substantial level of industrialization.

Figure 2: Maturity of businesses in industrial development

Source: Authors

The COVID-19 pandemic can have either U- or V-shaped impacts on countries’ paths of industrialization. However, we argue that the risk that developing countries might never attain higher levels of industrialization is greater than ever before. This is because in view of the current market contractions, more integrated firms have lower per-unit costs than specialized (but more distant) suppliers. (Milberg and Winkler, 2010). Consequently, more distant suppliers (in developing countries) may capture less volume and value in global production and trade.

This may have two repercussions for the paths of industrialization of developing countries. Firstly, countries that have already started industrializing may be forced to veer off that path prematurely. This might be the case, for example, because they dropped out of certain supply chain relationships during the COVID-19 lockdown and cannot re-join those GVCs, or because value chain segments have moved out of developing and (back) to industrialized countries. The latter may also apply to LDCs that have barely started industrializing; consequently, they lose out on industrial development altogether.

How to prepare for what is to come

Companies have responded to the COVID-19 pandemic in various ways, for example, by addressing immediate cash-flow challenges, namely by cutting costs and seeking debt relief and compensation from their governments, or by repurposing their production lines to manufacture essential goods as well as by introducing teleworking and e-commerce in their day-to-day business. However, this may

not be enough to recover. Likewise, government policies to respond to health and economic emergencies, civil unrest, food supply shortages and dawning bankruptcies of businesses are only a necessary first step, but not sufficient to bring about a full-fledged recovery.

What industry now needs is a policy agenda that encourages resilient economic growth and long-term job creation. (Mendiluce, 2020) Indeed, thus far policy responses to COVID-19 have focused on ensuring continued operations of manufacturing firms and on mobilizing manufacturing towards the production of critical supplies. More emphasis needs to be put on post-crisis manufacturing growth and on measures that support business resumption. Opportunities for firms in developing countries must be secured so they can continue to participate in GVCs to reap sufficient benefits to develop and reorient their businesses for transformation.

Higher dependence on value chains could create lock-in effects for companies in developing countries, i.e. export-oriented industrialization may be a less viable vehicle towards development. (Rodrik, 2020) Following the argument of not putting all eggs in one basket, developing countries should avoid putting all their resources at the disposal of a few global buyers and should leave room to reinvent their product mix, engage in south-south trade and invest in participation in alternative GVCs where higher revenues can be accrued to justify the use of local resources beyond the internal rate of investment which had not factored in wider social costs and benefits. Dependence on individual products and value chain tiers should also make room for more diversified participation in more technologically advanced tiers of GVCs, where risks can be spread and higher value added can be captured. Policies must also focus on state support to increase competitiveness in strategically important industries so countries do not deindustrialize.

This calls for an active and involved state to assist industrial firms in their recovery efforts in the post-COVID-19 era and to support the reorientation of production towards markets with higher potentials and where the net benefits of participation in GVCs are positive. This can only be achieved if, in the medium- to long-term, there is investment in new business processes and in technological innovation. This is what ultimately lifts developing countries out of poverty and brings prosperity in all its positive facets.

Disclaimer: This opinion piece provides information about a situation that is rapidly evolving. As the circumstances and impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are continuously changing, the interpretation of the information presented here may also have to be adjusted in terms of relevance, accuracy and completeness. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNIDO (read more).