Manufacturing firms shouldn’t fear the true cost of fuel – here’s why

08 April 2021 Nicola Cantore, Massimiliano Calì, Jenny Larsen, Juergen Amann, Valentin Todorov and Charles Fang Chin Cheng

Story by Nicola Cantore, Massimiliano Calì, Jenny Larsen, Juergen Amann, Valentin Todorov and Charles Fang Chin Cheng

Main picture by Juozas Šalna, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Fresh UNIDO-led research in collaboration with the World Bank provides concrete evidence that removing fossil fuel subsidies would not only make environmental sense but would also improve firms’ economic performance. New firm-level data from Oman show that higher fuel prices are not a drag on competitiveness. In fact, reducing subsidies and allowing fuel prices to rise could ultimately aid the post-COVID-19 recovery. This is because, according to the data studied, higher fuel prices drive business upgrading, leading to a boost in productivity. They could also encourage manufacturing companies to switch to the kind of long-term sustainable efficiency practices needed to stop climate change.

There is no shortage of evidence on why governments should ditch fossil fuel subsidies. Artificially low prices prompt increased consumer demand and so more environmentally harmful fuels are produced, adding to air pollution and CO2 emissions. Subsidies also deter industry from putting energy efficiency measures in place and may delay moves to invest in more efficient machinery, which could harm long-term industrial competitiveness. From an economic welfare point of view, they misallocate public funds that could be better directed for social or other economic use.

Yet, globally government support for carbon-based industries still runs into hundreds of billions of dollars. If externalities such as pollution and climate change are included, the true cost comes in at over $5 trillion (IMF). The dramatic drop in oil prices in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic handed cash-strapped governments the perfect opportunity to act. But, so far, progress remains too slow, and some countries that embarked on reform over the past year already appear to be backtracking. This is because, despite the enormous environmental and economic costs of retaining fossil fuel subsidies, removing them remains politically tricky.

In many oil-rich economies these subsidies translate into a cash transfer to consumers and businesses alike. For consumers, especially those in low-income households, the guarantee of cheap prices at the pump is often seen as a necessary and welcome state benefit when provision of essential services such as health and education is lacking.

For industry, which is frequently handed an even more generous subsidy on fuel, the belief persists that high energy costs will hurt competitiveness. Profit-maximizing firms worry that any hike would hit their bottom line; more expensive energy inputs mean performance suffers and competitiveness falls, or so the argument goes. In industrializing countries, where access to competitively priced energy is seen as key to industrial growth and vital in sectors looking to access tough global markets, the idea is particularly hard to sell. This view is held more fiercely in manufacturing, where energy often represents a sizeable slice of overall production costs. The damage done by the current crisis has done nothing to dampen such concerns.

The issue goes to the heart of a question that has long vexed economists: is there a trade-off between environmental regulation and economic performance? Will allowing energy prices to reflect their true cost harm the competitiveness of firms?

As far back as the 1990s, the Porter Hypothesis challenged the generally accepted idea that there is a clear trade-off, arguing that environmental regulation resulting in higher fuel prices would not necessarily damage the ability of businesses to compete. Instead, industries may compensate for the higher costs through innovation and upgrading, which could improve their long-term competitiveness.

One problem to date has been a lack of country studies providing solid, empirical evidence at firm level to show how industries deal with higher energy costs, and whether they are able to successfully absorb them without losing competitiveness.

A new UNIDO-led study conducted on data from Oman, a country on the south-eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, helps to fill this gap. It provides clear information from over 3,600 manufacturing firms on the type of measures taken to cope with the rise in fuel prices resulting from a subsidy reform. It demonstrates empirically that higher fuel prices, far from harming competitiveness of firms, in fact improve their productivity and efficiency.

In 2015, the Omani government reformed its longstanding fuel subsidy system following a severe drop in net oil revenues. As a result, the value of the subsidies fell from $1.1 billion in 2014 to $54 million in 2017, helping to shore up dwindling state coffers. The reforms were accompanied by government programmes to help small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to improve efficiency and sustainability, including support for a digital transformation.

The UNIDO paper, Switching it up: The effect of energy price reforms in Oman, is the first to look at the impact of fuel prices on the manufacturing sector, tracking developments in companies between 2012 and 2017 through the Omani Annual Industrial Survey. Results indicate that the rise in fuel prices led to improvements in productivity and efficiency as firms switched to digital technology, and information and communications technology (ICT) equipment. For example, according to the data, a 10 per cent rise in fuel prices led to an increase in labour productivity of 4.1 to 4.6 per cent.

Globally, almost 45 per cent of energy consumed by industry is energy produced by fossil fuels for industrial processes, such as the generation of heat for drying, melting and cracking. Only about 20 per cent consists of electricity. In Oman, the research found that firms responded to the price hike by switching from fossil fuels to electricity. Results showed that a 10 per cent rise in fuel prices led to a 4.7 per cent rise in the quantity of electricity used and a 3.6 per cent drop in the amount of fossil fuels used. These changes resulted from firms: 1) using fuel more efficiently; 2) investing in computers and electronic devices to improve energy management and to optimize the use of inputs; and 3) replacing their fuel-powered electricity generators with a connection to a modern electricity grid.

These results chime with another recent UNIDO-World Bank study on Indonesia and Mexico, which found that an increase in fuel prices generated a drop in fuel consumption and an increase in electricity usage. This pattern was the result of firms replacing obsolete fuel-powered capital equipment with more productive electricity-powered capital equipment.

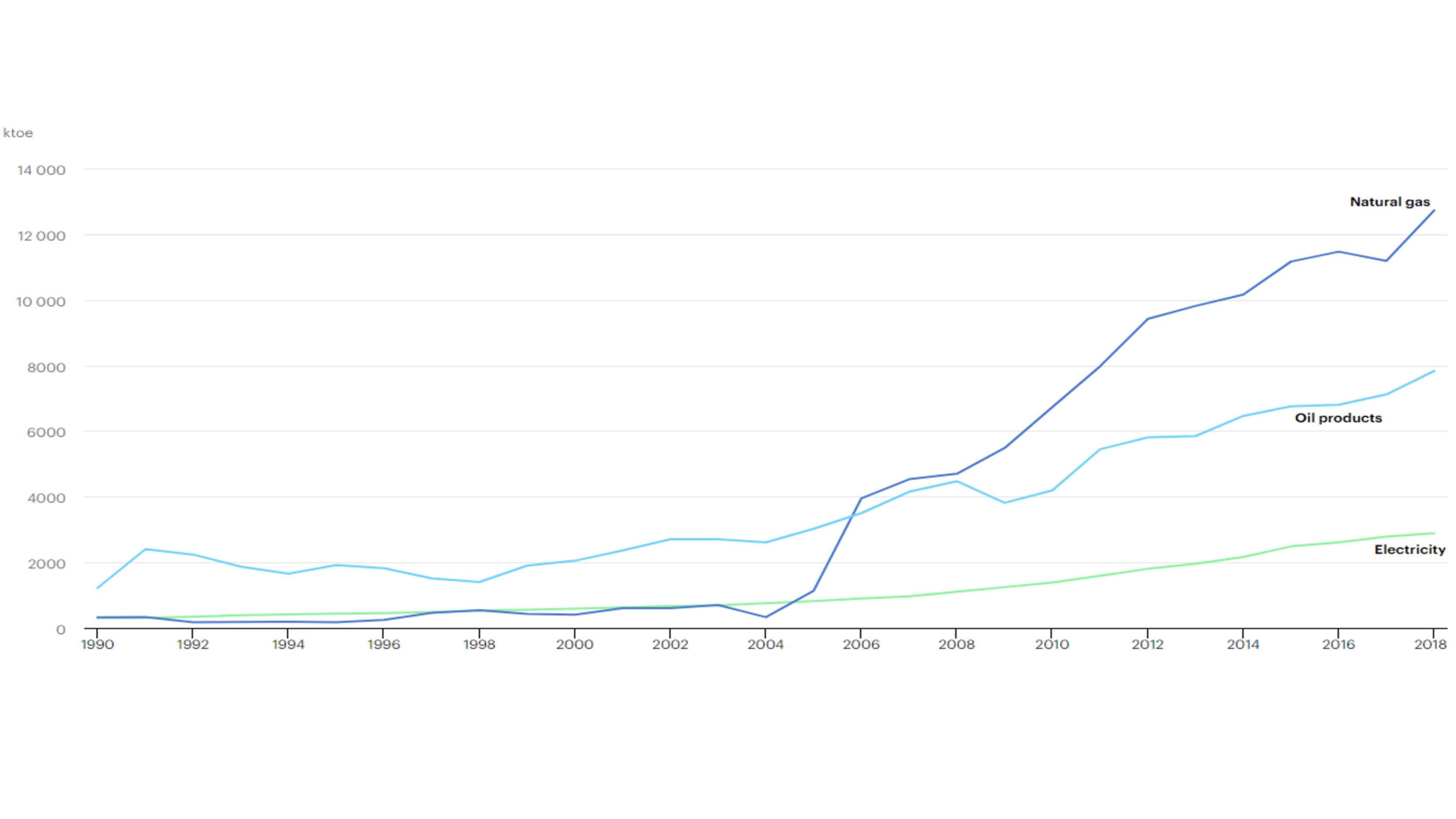

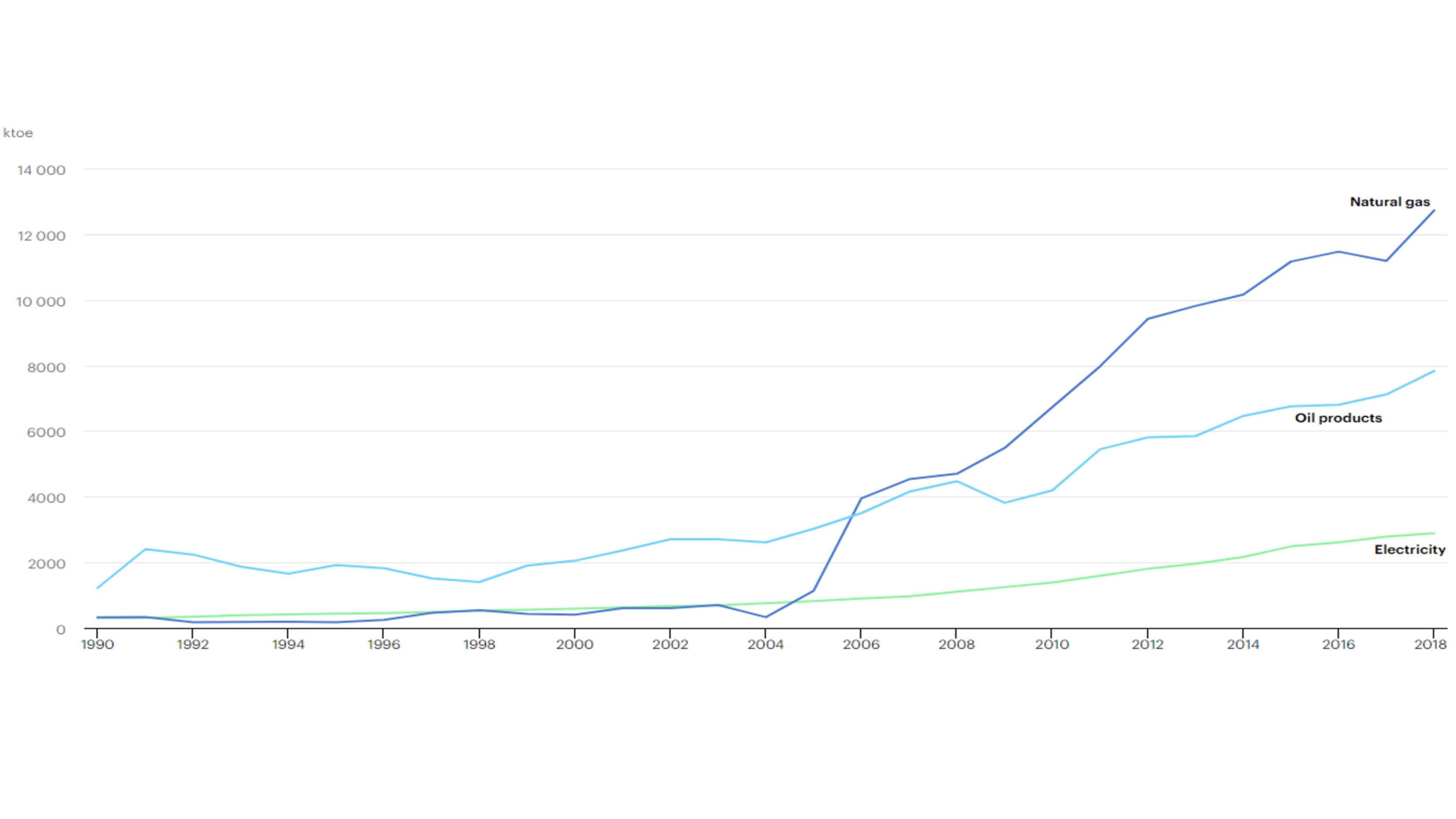

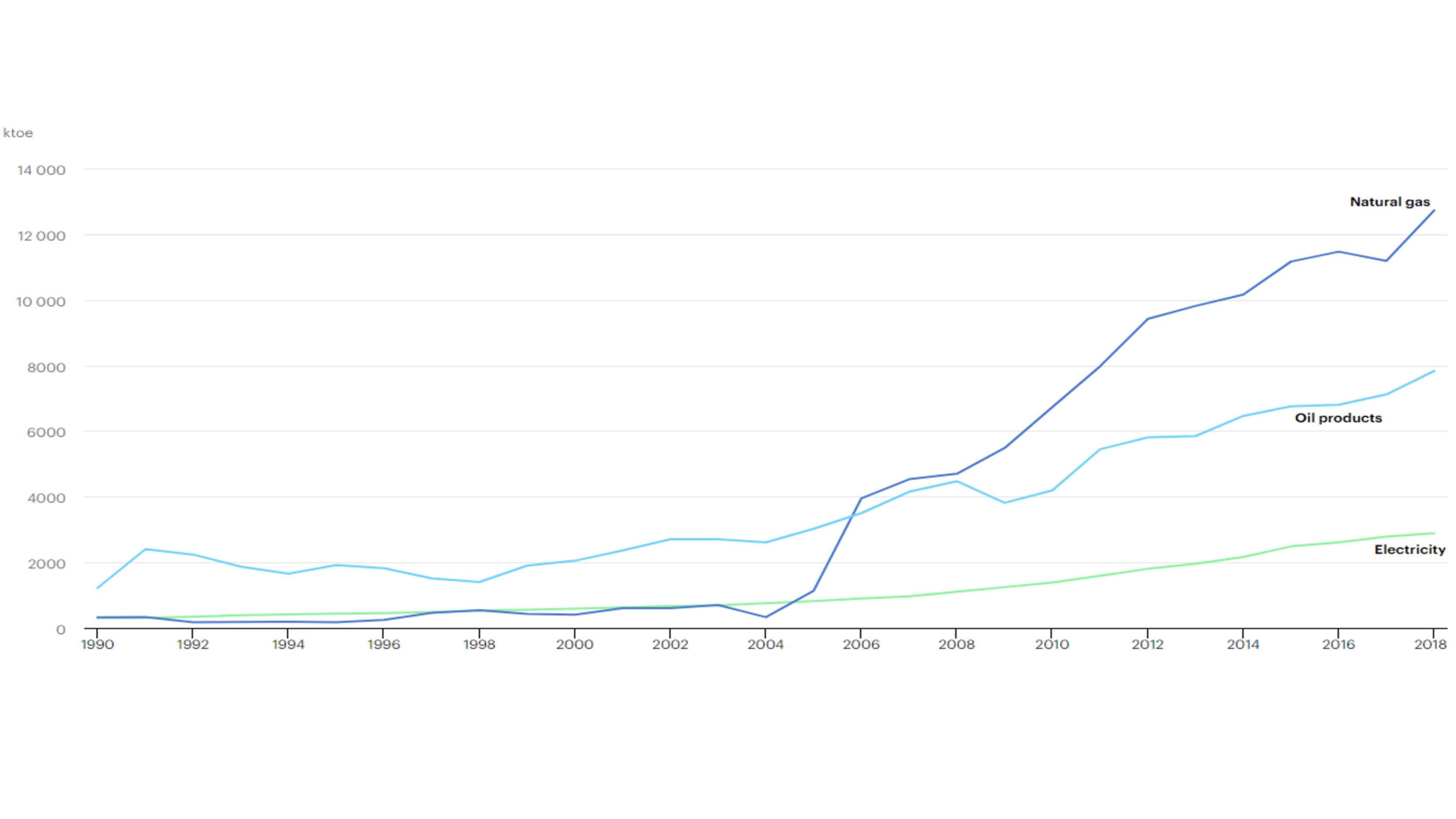

Figure 1, below, shows that between 1990 and 2018, Oman saw a strong increase in consumption of fuels (natural gas and oil products) with weak growth in electricity consumption suggesting that higher fuel prices could trigger an untapped potential of greater electricity penetration.

Figure 1. Total energy consumption in Oman 1990 - 2018. Source: IEA

The findings signal a potential way ahead for other oil economies in the Middle East and beyond, suggesting that policymakers need not shy away from bold action for fear of negative economic consequences, especially at a time when many are struggling to find resources to fight the pandemic.

On the contrary, the study lends more power to the Porter Hypothesis, bolstering the argument that axing fuel subsidies would encourage plant modernization and help to remove price impediments against the adoption of green technologies and efficiency measures needed to permanently reduce CO2 emissions.

It looks increasingly like the global drop in emissions in 2020 will be a blip. In a data report issued in March, the International Energy Agency (IEA) noted a resurgence in energy-related emissions after a historic 6 per cent fall in 2020. A return to business as usual would pose a serious threat to global ambitions to reach net zero by mid-century.

To have any hope of meeting emissions targets, fuel prices must be allowed to move towards their market level to create the business environment needed for speedier adoption of green energy. In its latest submission to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the Omani government acknowledged that there is untapped potential in renewable electricity.

Empirical evidence from Oman lets us see what the direction other countries should take. Kicking the subsidy habit for good is how we can finally create the competitive and sustainable industries needed to fight the negative economic impacts of the pandemic and to build a long-term recovery.

Disclaimer: the opinions are of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the affiliated institutions.

_____________________________________________

Authors: